Topics

When talking about Optics and Photonics it is frequent to hear about optical fibres, for example, when referring to the telecommunications optical fibre (“superfast fibre broadband”) or even sensors made with optical fibres.

In my previous blog posts, I mention optical fibre applied to sensors and the Quantum Communications field.

In this blog post I will mention some different types of optical fibres, how to use them as sensors, some applications and why optical fibres are important, not only in the Optics and Photonics field but also in other fields such as spectroscopy and medicine.

What is an optical fibre?

A simple description of an optical fibre it is a cylindrical waveguide [1], the fibre will act as a guide for light and it can be made of different materials, such as silica or polymeric materials. For example, in my first Physics project in Portugal, I worked with plastic optical fibre. The aim was to develop a sensor to see the progress of a winemaking process [2].

An optical fibre is composed of a core, a cladding and a coating which gives the fibre support and protects the cladding of the optical fibre. When describing silica optical fibres there can be single-mode and multimode fibres and the main geometrical difference is the size of the core [3]. These are usually called conventional optical fibres [4].

The single mode optical fibres are currently used in optical fibre sensors in applications such as measurement and monitoring of strain, temperature, displacement, bending or torsion, vibration and acceleration, rotation, current or voltage and chemical/detection [5]. The optical fibre has also been used in communications, as we saw in the previous blog posts, due to some important characteristics such as vast potential bandwidth, small size and weight, electrical isolation, immunity to interference and crosstalk, signal security, low transmission loss, ruggedness and flexibility, system reliability, ease of maintenance and potential low cost [6].

So, what else exists besides conventional optical fibres?

During my PhD I worked with microstructured optical fibre. This means that the core of the fibre does not have to be silica based and can actually be hollow. Also, the cladding may contain complex structures at the micro-scale (usually silica based). If that cladding microstructure is periodic with air holes, the fibre are usually referred to as a Photonic Crystal Fibres. These fibres appeared in the 1990s and showed flexibility in terms of application due to the possibility to tailor the optical waveguide parameters, this is, to create a fibre that will guide the wavelengths as desired [7]. These fibres are usually made of silica since the fabrication process is well stablished and achieves good results [8].

But why have the non-conventional optical fibres emerged?

One of the reasons is to work with new fibre design is for applications which use a wavelength region that is not possible to achieve with a conventional optical fibre. For example, in order to detect biological molecular species it is necessary to work in the infrared region characterised by the strong vibration absorption lines of these various molecules. Measuring in this region with optical fibre sensors can enable applications in spectroscopy and medicine [9].

The problem is that silica glass strongly absorbs those wavelengths making difficult to work with the conventional fibres with a solid silica glass core for this purpose. To overcome that problem, hollow core fibres emerged. These fibres allow the guidance in the infrared region as the light travels in a hollow , non-absorbing core, therefore making practical optical fibre sensors possible. Although alternative materials have also been studied that do not strongly absorb in the infrared region, the fabrication process is much more difficult than using silica glass [9].

Since hollow core fibres allow this great advantage with low loss and good light guidance characteristics [9], new fibres were studied and developed. For example, Photonic Cristal fibres have been reported as promising alternatives for both optical communications and optical sensing and the possibility to fill the core with fluid has been considered either for gas or liquid sensors [10]. The fibres have also shown the flexibility to vary the size of the cladding holes as well as the location, with it being possible to select the fibre transmission spectrum [11].

Which are the main hollow-core fibre types?

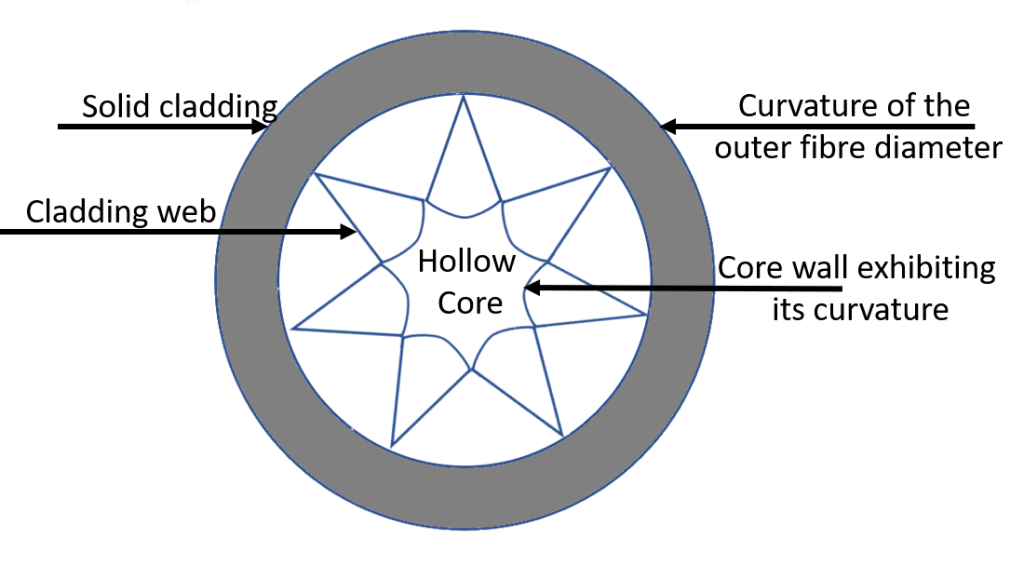

There can be photonic bandgap fibres [8], Omniguide fibres [12], kagome lattice fibres [13] and negative curvature fibres [14]. The difference is not only size but also shape and consequently the way they will guide the light i.e. based on the structure of the fibre, the light guiding mechanism will be different. The first reported negative curvature effect was in 2013 where it was shown that it has influence on the fibre transmission loss and its modal properties [14].

It should be noted that the negative curvature refers to the shape that the core-cladding interface exhibits when compared to the curvature of the outer fibre diameter, different orientation therefore negative curvature [15], see scheme in Figure 1.

During my PhD I worked with negative curvature fibres, taking advantage not only of the negative curvature effect, which is reduces the optical loss, [16] but also of its simpler structure [17].

Can we use those fibres directly as sensors?

It is important to functionalise the fibres so that they can be used as optical fibre sensors. Why? If we want to detect gas molecules, for example, it is important to increase the access of the substance we want to measure to the hollow core to enhance the interaction of the measurand with the light and consequently to improve the response time of the sensor [18].

So, how can we functionalise the fibres?

Methods to modify the fibre to allow access to the core are needed. But, as we have seen above, since the microstructure will have impact on the light guidance, it is necessary to modify the fibre but preserve its microstructure.

During my PhD I explored the fabrication route to achieve the full potential of these interesting fibres. Femtosecond laser machining was chosen as it has advantages including the ability for inscription without pre-processing or special core doping and its inherent flexibility of being a non-thermal process. This method can allow structures to be inscribed with an almost negligible heat-affected zone. If you are curious about this process, as well as about hollow core negative curvature fibres, check out this paper.

All these different optical fibres with their vast range of characteristics and applications contribute, not only directly to the field of Optics and Photonics but also provide immense potential and impact to open new areas across many diverse fields.

Blog Post Review

This blog post was reviewed by Professor Jonathan D. Shephard to whom I would like to thank.

References

- B. E. A. Saleh and M. C. Teich, “Fiber Optics,” in Fundamentals of Photonics (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2001), pp. 272–309.

- C. Novo, L. Bilro, R. Ferreira, N. Alberto, P. Antunes, R. Nogueira, and J. L. Pinto, “Optical fibre monitoring of Madeira wine estufagem process,” in 8th Iberoamerican Optics Meeting and 11th Latin American Meeting on Optics, Lasers, and Applications, M. F. P. C. M. Costa, ed. (SPIE, 2013), 8785, pp. 1611–1615.

- “How Fiber Optics Work” in “How Stuff Works”

- J. C. Knight, T. A. Birks, R. F. Cregan, P. S. J. Russell, and J.-P. de Sandro, “Photonic crystals as optical fibres – physics and applications,” Opt. Mater. (Amst). 11(2), 143–151 (1999).

- B. Lee, “Review of the present status of optical fiber sensors,” Opt. Fiber Technol. 9(2), 57–79 (2003).

- S. J. M, Optical Fiber Communications: Principles and Practice (Pearson Education, 2009).

- F. Berghmans, T. Geernaert, T. Baghdasaryan, and H. Thienpont, “Challenges in the fabrication of fibre Bragg gratings in silica and polymer microstructured optical fibres,” Laser Photonics Rev. 8(1), 27–52 (2014).

- J. Knight, “Photonic crystal fibres,” Nature 424(6950), 847–851 (2003).

- F. Yu, W. J. Wadsworth, and J. C. Knight, “Low loss silica hollow core fibers for 3–4 μm spectral region,” Opt. Express 20(10), 11153–11158 (2012).

- T. M. Monro, Y. D. West, D. W. Hewak, N. G. R. Broderick, and D. J. Richardson, “Chalcogenide holey fibres,” Electron. Lett. 36(24), 1998–2000 (2000).

- A. M. R. Pinto and M. Lopez-Amo, “Photonic crystal fibers for sensing applications,” J. Sensors 2012, (2012).

- T. Engeness, M. Ibanescu, S. Johnson, O. Weisberg, M. Skorobogatiy, S. Jacobs, and Y. Fink, “Dispersion tailoring and compensation by modal interactions in OmniGuide fibers,” Opt. Express 11(10), 1175–96 (2003).

- G. J. Pearce, G. S. Wiederhecker, C. G. Poulton, S. Burger, and P. S. J. Russell, “Models for guidance in kagome-structured hollow-core photonic crystal fibres,” Opt. Express 15(20), 12680–12685 (2007).

- F. B. B. Debord, M. Alharbi, T. Bradley, C. Fourcade-Dutin, Y.Y. Wang, L. Vincetti, F. Gérôme, “Hypocycloid-shaped hollow-core photonic crystal fiber Part I: Arc curvature effect on confinement loss,” Opt. Express 21(23), 28597–21 (2013).

- C. Novo, D. Choudhury, B. Siwicki, R. Thomson, and J. Shephard, “Femtosecond Laser Machining of Hollow-Core Negative Curvature Fibres,” Opt. Express 28(17), 25491–25501 (2020).

- C. Wei, R. J. Weiblen, C. R. Menyuk, and J. Hu, “Negative curvature fibers,” Adv. Opt. Photonics 9(3), 504–561 (2017).

- C. C. Novo, A. Urich, D. Choudhury, R. Carter, D. P. Hand, R. R. Thomson, F. Yu, J. C. Knight, S. Brooks, S. Mcculloch, and J. D. Shephard, “Negative curvature fibres: exploiting the potential for novel optical sensors,” Proc. SPIE 9634, 963454–963455 (2015).

- H. Lehmann, H. Bartelt, R. Willsch, R. Amezcua-Correa, and J. C. Knight, “In-line gas sensor based on a photonic bandgap fiber with laser-drilled lateral microchannels,” IEEE Sens. J. 11(11), 2926–2931 (2011).